Désolé, cet article est seulement disponible en Anglais Américain. Pour le confort de l’utilisateur, le contenu est affiché ci-dessous dans une autre langue. Vous pouvez cliquer le lien pour changer de langue active.

By Yoeri Geutskens

This article was first published in December 2015, but has been updated post-CES 2016 (corrections on Dolby Vision, UHD Alliance's "Ultra HD Premium" specification and the merging of Technicolor and Philips HDR technologies).

A lot has been written about HDR video lately, and from all of this perhaps only one thing becomes truly clear – that there appear to be various standards to choose from. What’s going on in this area in terms of technologies and standards? Before looking into that, let’s take a step back and look at what HDR video is and what’s the benefit of it.

Since 2013, Ultra HD or UHD has come up as a major new consumer TV development. UHD, often also referred to as ‘4K’, has a resolution of 3,840 x 2,160 – twice the horizontal and twice the vertical resolution of 1080p HDTV, so four times the pixels. UHD has been pushed above all by TV manufacturers looking for new ways to entice consumers to buy new TV sets. To appreciate the increased resolution of UHD, one needs to have a larger screen or a smaller viewing distance but it serves a trend towards ever larger TV sizes.

While sales of UHD TV sets are taking off quite prosperously, the rest of the value chain isn’t following quite as fast. Many involved feel the increased spatial resolution alone is not enough to justify the required investments in production equipment. Several other technologies promising further enhanced video are around the corner however. They are:

- High Dynamic Range or HDR

- Deep Color Resolution: 10 or 12 bits per subpixel

- Wide Color Gamut or WCG

- High Frame Rate or HFR: 100 or 120 frames per second (fps)

As for audio, a transition from conventional (matrixed or discrete) surround sound to object-based audio is envisaged for the next generation of TV.

Of these technologies, the first three are best attainable in the short term. They are also interrelated.

So what does HDR do? Although it’s using rather different techniques, HDR video is often likened to HDR photography as their aims are similar: to capture and reproduce scenes with a greater dynamic range than traditional technology can, in order to offer a more true-to-life experience. With HDR, more detail is visible in images that would otherwise look either overexposed, showing too little detail in bright areas, or underexposed, showing too little detail in dark areas.

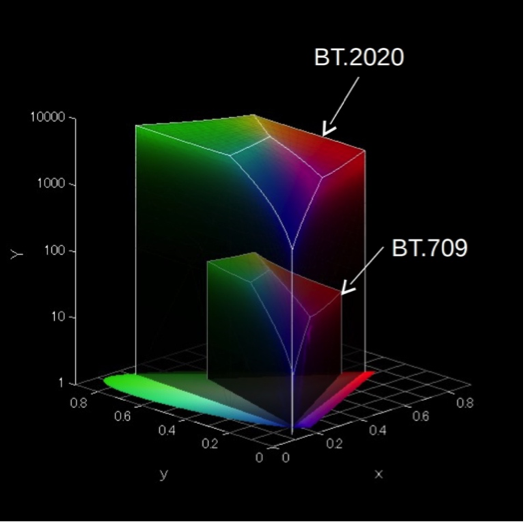

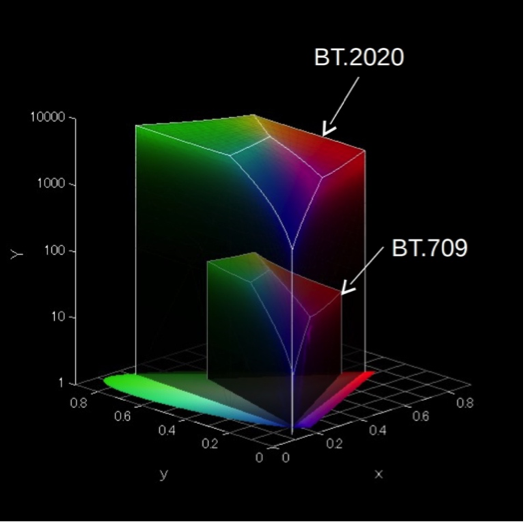

HDR video is typically combined with a feature called Wide Color Gamut or WCG. Traditional HDTVs use a color space referred to as Rec.709, which was defined for the first generations of HDTVs which used CRT displays. Current flat panel display technologies like LCD and OLED can produce a far wider range of colors and greater luminance, measured in ‘nits’. A nit is a unit for brightness, equal to candela per square meter (cd/m2). To accommodate this greater color gamut, Rec.2020 color space was defined. No commercial display can fully cover this new color space but it provides room for growth. The current state of the art of color gamut for displays in the market is a color space called DCI-P3 which is smaller than Rec.2020 but substantially larger than Rec.709.

To avoid color banding issues that could otherwise occur with this greater color gamut, HDR/WCG video typically uses a greater sampling resolution of 10 or 12 bits per subpixel (R, G and B) instead of the conventional 8 bits, so 30 or 36 bits per pixel rather than 24.

Color/luminance volume: BT.2020 (10,000 nits) versus BT.709 (100 nits); Yxy

Image credit: Sony

The problem with HDR isn’t so much on the capture side nor on the rendering side – current professional digital cameras can handle a greater dynamic range and current displays can produce a greater contrast than the content chain in between can handle. It’s the standards for encoding, storage, transmission and everything else that needs to happen in between that are too constrained to support HDR.

So what is being done about this? A lot, in fact. Let’s look at the technologies first. A handful of organizations have proposed technologies for describing HDR signals for capture, storage, transmission and reproduction. They are Dolby, SMPTE, Technicolor, Philips, and BBC together with NHK. Around the time of CES 2016, Technicolor and Philips have announced they are going to merge their HDR technologies.

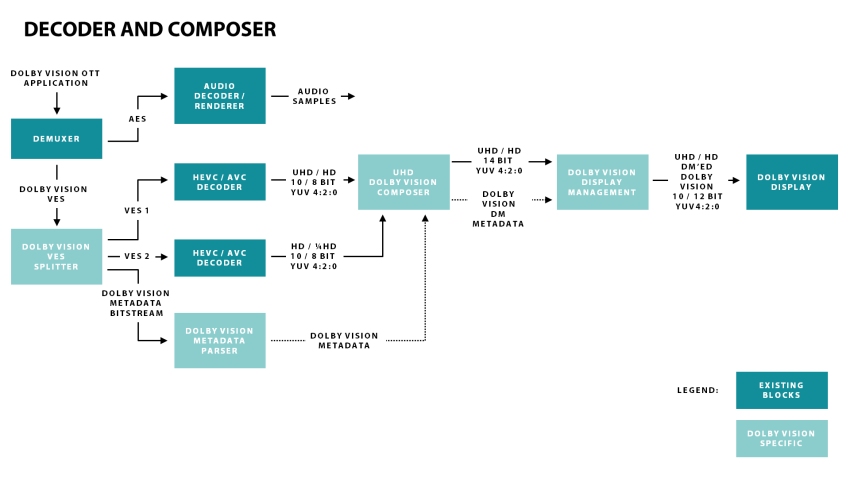

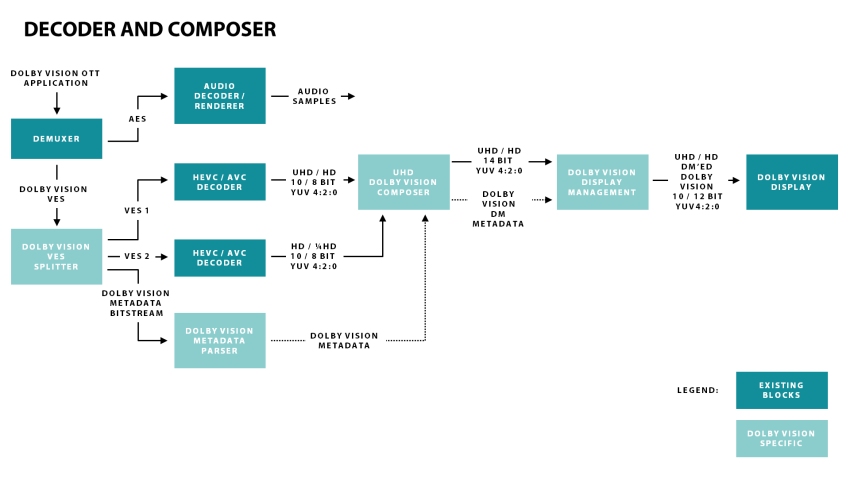

Dolby’s HDR technology is branded Dolby Vision. One of the key elements of Dolby Vision is the Perceptual Quantizer EOTF which has been standardized by SMPTE as ST 2084 (see box: SMPTE HDR Standards) and mandated by the Blu-ray Disc Association for the new Ultra HD Blu-ray format. The SMPTE ST 2084 format can actually contain more picture information than TVs today can display but because the information is there as manufacturers build better TVs the content has the potential to look better as the new, improved display technologies come to market. Dolby Vision and HDR10 use the same SMPTE 2084 standard making it easy for studios and content producers to master once and deliver to either HDR10 or, with the addition of dynamic metadata, Dolby Vision. The dynamic metadata is not an absolute necessity, but using it guarantees the best results when played back on a Dolby Vision-enabled TV. HDR10 uses static metadata which ensures it will still look good – far better than Standard Dynamic Range (SDR). Even using no metadata at all, SMPTE 2084 can work at an acceptable level just as other proposed EOTFs without metadata do.

For live broadcast Dolby supports both single and dual layer 10-bit distribution methods and has come up with a single workflow that can simultaneously deliver an HDR signal to the latest generation and future TVs and a derived SDR signal to support all legacy TVs. The signal can be encoded in HEVC or AVC. Not requiring dual workflows will be very appealing to all involved in content production and the system is flexible to let the broadcaster choose where to derive the SDR signal. If it’s done at the head-end they can choose to simply simulcast it as another channel or convert the signal to dual-layer single stream signal at the distribution encoder for transmission. Additionally the HDR-to-SDR conversion can be built into set-top boxes for maximum flexibility without compromising the SDR or HDR signals. Moreover, the SDR distribution signal that’s derived from the HDR original using Dolby’s content mapping unit (CMU) is significantly better in terms of detail and color than one that’s captured natively in SDR, as Dolby demonstrated side by side at IBC 2015. The metadata is only produced and multiplexed into the stream at the point of transmission, just before or in the final encoder – not in the baseband workflow. Dolby uses 12-bit color depth for cinematic Dolby Vision content to avoid any noticeable banding but the format is actually agnostic to different color depths and works with 10-bit video as well. In fact, Dolby recommends 10-bit color depth for broadcast.

High-level overview of Dolby Vision dual-layer transmission for OTT VOD;

other schematics apply for OTT live, broadcast, etc. Image credit: Dolby Labs Dolby Vision white paper

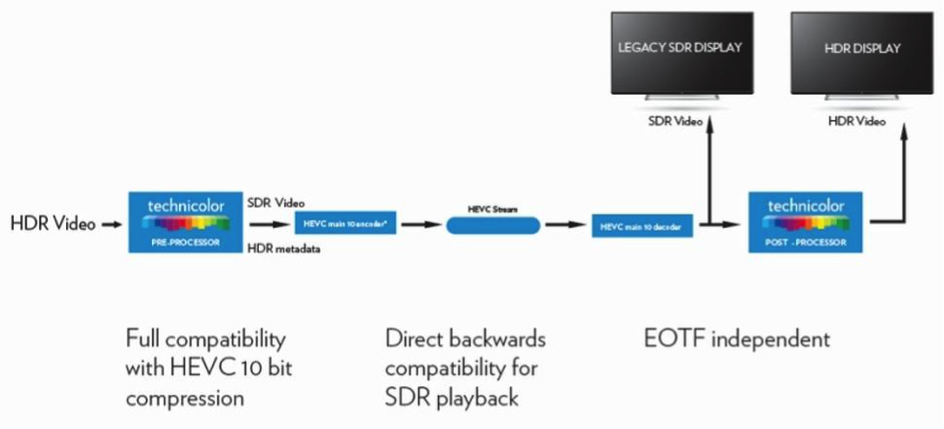

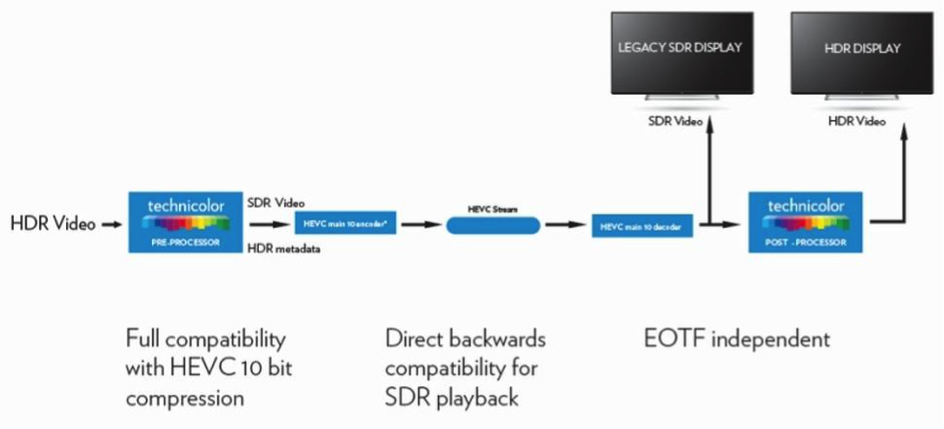

Technicolor has developed two HDR technologies. The first takes a 10-bit HDR video signal from a camera and delivers a video signal that is compatible with SDR as well as HDR displays. The extra information that is needed for the HDR rendering is encoded in such a way that it builds on top of the 8-bit SDR signal but SDR devices simply ignore the extra data.

Image credit: Technicolor

The second technology is called Intelligent Tone Management and offers a method to ‘upscale’ SDR material to HDR, using the extra dynamic range that current-day capture devices can provide but traditional encoding cannot handle, and providing enhanced color grading tools to colorists. While it remains to be seen how effective and acceptable the results are going to be, this technique has the potential to greatly expand the amount of available HDR content.

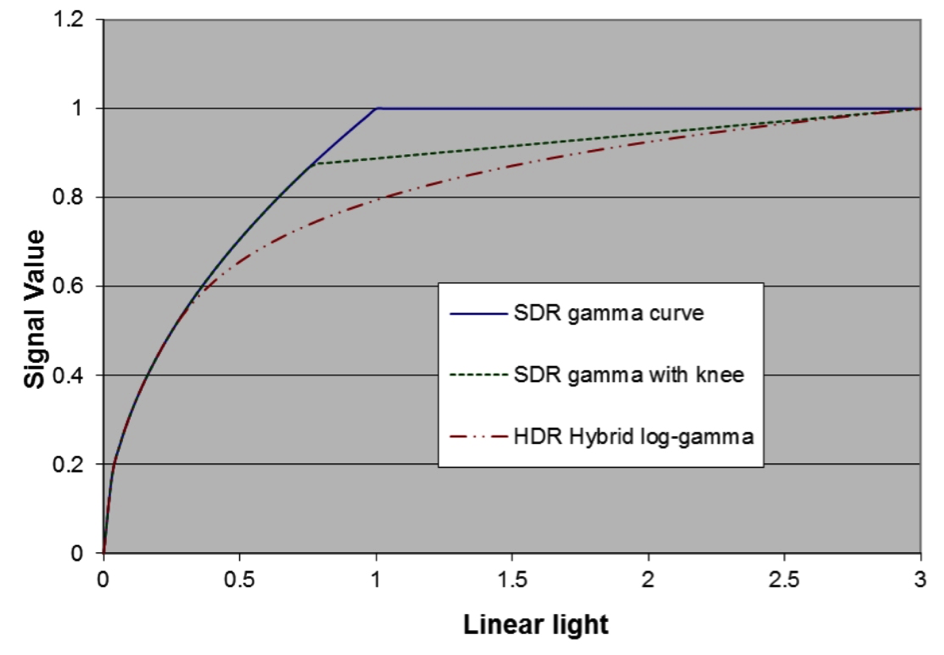

Having a single signal that delivers SDR to legacy TV sets (HD or UHD) and HDR to the new crop of TVs is also the objective of what BBC’s R&D department and Japan’s public broadcaster NHK are working on together. It’s called Hybrid Log Gamma or HLG. HLG’s premise is an attractive one: a single video signal that renders SDR on legacy displays but HDR on displays that can handle this. HLG, BBC and NHK say, is compatible with existing 10-bit production workflows and can be distributed using a single HEVC Main 10 Profile bitstream.

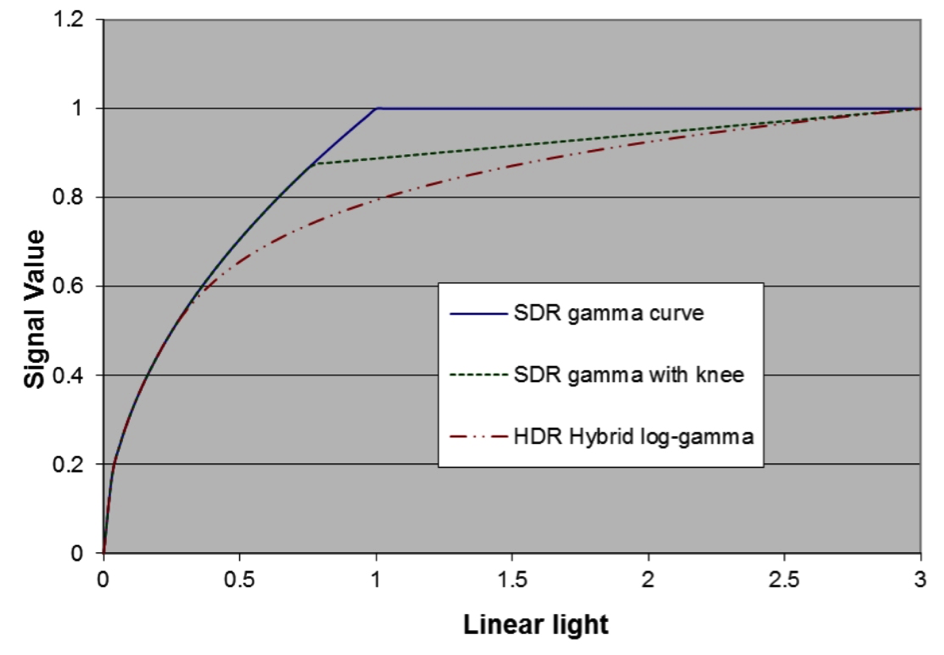

Depending on whom you ask HLG is the best thing since sliced bread or a clever compromise that accommodates SDR as well as HDR displays but gives suboptimal results and looks great on neither. The Hybrid Log Gamma name refers to the fact that the OETF is a hybrid that applies a conventional gamma curve for low-light signals and a logarithmic curve for the high tones.

Hybrid Log Gamma and SDR OETFs; image credit: T. Borer and A. Cotton, BBC R&D

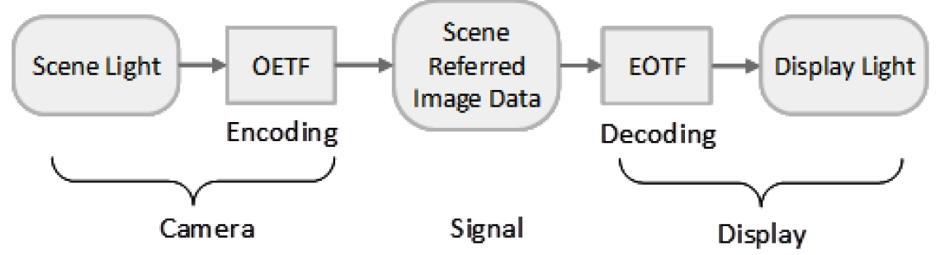

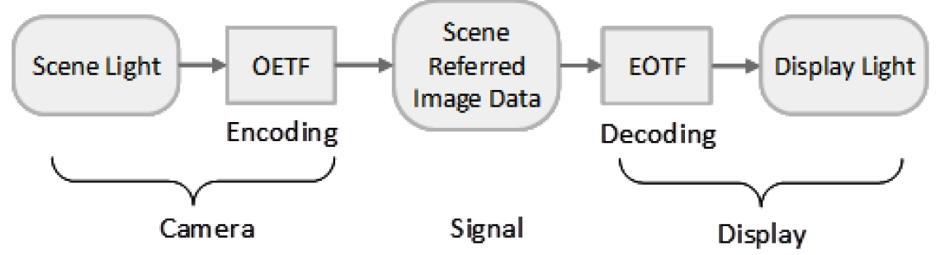

Transfer functions:

- OETF: function that maps scene luminance to digital code value; used in HDR camera;

- EOTF: function that maps digital code value to displayed luminance; used in HDR display;

- OOTF: function that maps scene luminance to displayed luminance; a function of the OETF and EOTF in a chain. Because of the non-linear nature of both OETF and EOTF, the chain’s OOTF also has a non-linear character.

Image credit: T. Borer and A. Cotton, BBC R&D

The EOTF for Mastering Reference Displays, conceived by Dolby and standardized by SMPTE as ST 2084 is ´display-referred'. With this approach, the OOTF is part of the OETF, requiring implicit or explicit metadata.

Hybrid Log Gamma (HLG), proposed by BBC and NHK, is a 'scene-referred' system which means the OOTF is part of the EOTF. HLG does not require mastering metadata so the signal is display-independent and can be displayed unprocessed on an SDR screen. |

The reasoning is simple: bandwidth is scarce, especially for terrestrial broadcasting but also for satellite and even cable, so transmitting the signal twice in parallel, in SDR and HDR, is not an attractive option. In fact, most broadcasters are far more interested in adding HDR to 1080p HD channels than in launching UHD channels, for exactly the same reason. Adding HDR is estimated to consume up to 20% extra bandwidth at most, whereas a UHD channel gobbles up the bandwidth of four HD channels. It’s probably no coincidence HLG technology has been developed by two broadcast companies that have historically invested a lot in R&D. Note however that the claimed backwards compatibility of HLG with SDR displays only applies to displays working with Rec.2020 color space, i.e. Wide Color Gamut. This more or less makes its main benefit worthless.

ARIB, the Japanese organization that’s the equivalent of DVB in Europe and ATSC in North America, has standardized upon HLG for UHD HDR broadcasts.

The DVB Project meanwhile has recently announced that UHD-I phase 2 will actually include a profile that adds HDR to 1080p HD video – a move advocated by Ericsson and supported by many broadcasters. Don’t expect CE manufacturers to start producing HDTVs with HDR however. Such innovations are likely to end up only in the UHD TV category, where the growth is and any innovation outside of cost reductions takes place.

This means consumers will need a HDR UHD TV to watch HD broadcasts with HDR. Owners of such TV sets will be confronted with a mixture of qualities – plain HD, HD with HDR, plain UHD and UHD with HDR (and WCG), much in the same way HDTV owners may watch a mix of SD and HD television, only with more variations.

The SMPTE is one of the foremost standardization bodies active in developing official standards for the proposed HDR technologies. See box ‘SMPTE HDR standards’.

| SMPTE HDR Standards

ST 2084:2014 - High Dynamic Range EOTF of Mastering Reference Displays

- defines 'display referred' EOTF curve with absolute luminance values based on human visual model

- called Perceptual Quantizer (PQ)

ST 2086:2014 - Mastering Display Color Volume Metadata supporting High Luminance and Wide Color Gamut images

- specifies mastering display primaries, white point and min/max luminance

Draft ST 2094:201x - Content-dependent Metadata for Color Volume Transformation of High-Luminance and Wide Color Gamut images

- specifies dynamic metadata used in the color volume transformation of source content mastered with HDR and/or WCG imagery, when such content is rendered for presentation on a display having a smaller color volume

|

One other such body is the Blu-ray Disc Association (BDA). Although physical media have been losing some popularity with consumers lately, few people are blessed with a fast enough broadband connection to be able to handle proper Ultra HD video streaming, with or without HDR. Netflix requires at least 15 Mbps sustained average bitrate for UHD watching but recommends at least 25 Mbps. The new Ultra HD Blu-ray standard meanwhile offers up to 128 Mpbs peak bit rate. Of course one can compress Ultra HD signals but the resulting quality loss would defy the entire purpose of Ultra High Definition.

Ultra HD Blu-ray may be somewhat late to the market, with some SVOD streaming services having beat them to it, but the BDA deserves praise for not rushing the new standard to launch without HDR support. Had they done that, the format may very well have been declared dead on arrival. The complication, of course, was that there was no single agreed-upon standard for HDR yet. The BDA has settled on the HDR10 Media Profile (see box) as mandatory for players and discs with Dolby Vision and Philips’ HDR format as optional for players as well as discs.

HDR10 Media Profile

- EOTF: SMPTE ST 2084

- Color sub-sampling: 4:2:0 (for compressed video sources)

- Bit depth: 10 bit

- Color primaries: ITU-R BT.2020

- Metadata: SMPTE ST 2086, MaxFall (Maximum Frame Average Light Level), MaxCLL (Maximum Content Light Level)

Referenced by:

- Ultra HD Blu-ray spec (Blu-Ray Disc Association)

- HDR-compatible display spec (CTA; former CEA)

|

| UHD Alliance ‘Ultra HD Premium’ definition |

Display |

Content |

Distribution |

| Image resolution |

3840×2160 |

3840×2160 |

3840×2160 |

| Color Bit Depth |

10-bit signal |

Minimum 10-bit signal depth |

Minimum 10-bit signal depth |

| Color Palette |

Signal input: BT.2020 color representation

Display reproduction: More than 90% of P3 color space |

BT.2020 color representation |

BT.2020 color representation |

| High Dynamic Range |

SMPTE ST 2084 EOTF

A combination of peak brightness and black level either:

More than 1000 nits peak brightness and less than 0.05 nits black level

or

More than 540 nits peak brightness and less than 0.0005 nits black level |

SMPTE ST 2084 EOTF

Mastering displays recommended to exceed 1000 nits in brightness, less than 0.03 black level, minimum of DCI-P3 color space |

SMPTE ST 2084 EOTF |

The UHD Alliance mostly revolves around Hollywood movie studios and is focused on content creation and playback, guidelines for CE devices, branding and consumer experience). At CES 2016, the UHDA has announced a set of norms for displays, content end ‘distribution’ to deliver UHD with HDR, and an associated logo program. The norm is called ‘Ultra HD Premium’ (see box). Is it a standard? Arguably, yes. Does it put an end to any potential confusion over different HDR technologies? Not quite – while the new norm guarantees a certain level of dynamic range it does not specify any particular HDR technology, so all options are still open.

The Ultra HD Forum meanwhile focuses on the end-to-end content delivery chain including production workflow and distribution infrastructure.

In broadcasting we’ve got ATSC in North America defining how UHD and HDR should be broadcast over the air with the upcoming ATSC 3.0 standard (also used in South Korea) and transmitted via cable. Here, the SCTE comes into play as well. Japan has the ARIB (see above) and for most of the rest of the world, including Europe, there’s the DVB Project, part of the EBU, specifying how UHD and HDR should fit into the DVB standards that govern terrestrial, satellite and cable distribution.

In recent news, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) has launched a new Industry Specification Group (ISG) “to work on a standardized solution to define a scalable and flexible decoding system for consumer electronics devices from UltraHD TVs to smartphones” which will look at UHD, HDR and WCG. Founding members include telcos BT and Telefónica. The former already operates a UHD IPTV service; the latter is about to launch one.

Then there are CTA (Consumer Technology Association, formerly known as CEA) in the US and DigitalEurope dealing with guidelines and certification programs for consumer products. What specifications does a product have to support to qualify for ‘Ultra HD’ branding? Both have formulated answers to that question. It has not been a coordinated effort but fortunately they turn out to almost agree on the specs. Unity on a logo was not as feasible, sadly. The UHD Alliance has just announced they’ve settled on a definition of Ultra HD they’ll announce at CES, January 4th, 2016. One can only hope this will not lead to yet more confusion (and more logos) but I’m not optimistic.

By now, the CTA has also issued guidelines for HDR. DigitalEurope hasn’t yet. It’d be great for consumers, retailers and manufacturers alike if the two organizations could agree on a definition as well as a logo this time.

| Ultra HD display definition |

CTA definition |

DigitalEurope definition |

| Resolution |

At least 3840x2160 |

At least 3840x2160 |

| Aspect ratio |

16:9 or wider |

16:9 |

| Frame rate |

Supporting 24p, 30p and 60p |

24p, 25p, 30p, 50p, 60p |

| Chroma subsampling |

Not specified |

4:2:0 for 50p, 60p

4:2:2 for 24p,25p, 30p |

| Color bit depth |

Minimum 8-bit |

Minimum 8-bit |

| Colorimetry |

BT.709 color space; may support wider colorimetry standards |

Minimum BT.709 |

| Upconversion |

Capable of upscaling HD to UHD |

Not specified |

| Digital input |

One or more HDMI inputs supporting HDCP 2.2 or equivalent content protection. |

HDMI with HDCP 2.2 |

| Audio |

Not specified |

PCM 2.0 Stereo |

| Logo |

|

|

| CTA definition of HDR-compatible:

A TV, monitor or projector may be referred to as a HDR Compatible Display if it meets the following minimum attributes:

- Includes at least one interface that supports HDR signaling as defined in CEA-861-F, as extended by CEA-861.3.

- Receives and processes static HDR metadata compliant with CEA-861.3 for uncompressed video.

- Receives and processes HDR10 Media Profile* from IP, HDMI or other video delivery sources. Additionally, other media profiles may be supported.

- Applies an appropriate Electro-Optical Transfer Function (EOTF), before rendering the image.

CEA-861.3 references SMPTE ST 2084 and ST 2086. |

What are consumers, broadcasters, TV manufacturers, technology developers and standardization bodies to do right now?

I wouldn’t want to hold any consumer back but I couldn’t blame them if they decided to postpone purchasing a new TV a little longer until standards for HDR have been nailed. Similarly, for broadcasters and production companies it only seems prudent to postpone making big investments in HDR production equipment and workflows.

For all parties involved in technology development and standardization, my advice would be as follows. It’s inevitable we’re going to see a mixture of TV sets with varying capabilities in the market – SDR HDTVs, SDR UHD TVs and HDR UHD TVs, and that’s not even taking into consideration near-future extensions like HFR.

Simply ignoring some of these segments would be a very unwise choice: cutting off SDR UHD TVs from a steady flow of UHD content for instance would alienate the early adopters who bought into UHD TV already. The CE industry needs to cherish these consumers. It’s bad enough that those Brits who bought a UHD TV in 2014 cannot enjoy BT Sport’s Ultra HD service today because the associated set-top box requires HDCP 2.2 which their TV doesn’t support.

It is not realistic to cater to each of these segments with separate channels either. Even if the workflows can be combined, no broadcaster wants to spend the bandwidth to transmit the same channel in SDR HD and HDR HD, plus potentially SDR UHD and HDR UHD.

Having separate channels for HD and UHD is inevitable but for HDR to succeed it’s essential for everyone in the production and delivery chain that the HDR signal be an extension to the broadcast SDR signal and the SDR signal be compatible with legacy Rec.709 TV sets.

Innovations like Ultra HD resolution, High Dynamic Range, Wide Color Gamut and High Frame Rate will not come all at once with a big bang but (apart from HDR and WCG which go together) one at a time, leading to a fragmented installed base. This is why compatibility and ‘graceful degradation’ are so important: it’s impossible to cater to all segments individually.

What is needed now is alignment and clarity in this apparent chaos of SDOs (Standards Defining Organizations). Let’s group them along the value chain:

| Domain |

Production |

Compression |

Broadcast |

Telecom |

Media/ Streaming |

CE |

| SDO |

SMPTE, ITU-R |

MPEG , VCEG |

ATSC, SCTE, EBU/DVB, ARIB, SARFT |

ETSI |

BDA, DECE (UV), MovieLabs |

CTA, DigitalEurope, JEITA |

Within each segment, the SDOs need to align because having different standards for the same thing is counterproductive. It may be fine to have different standards applied, for instance if broadcasting uses a different HDR format than packaged media; after all, they have differing requirements. Along the chain, HDR standards do not need to be identical but they have to be compatible. Hopefully organizations like the Ultra HD Forum can facilitate and coordinate this between the segments of the chain.

If the various standardization organizations can figure out what HDR flavor to use in which case and agree on this, the future is looking very bright indeed.

Further reading:

Yoeri Geutskens has worked in consumer electronics for more than 15 years. He writes about high-resolution audio and video. You can follow him on Ultra HD and 4K on twitter @UHD4k.